Trust leaders Heather McNaughton and Caroline Pusey have shared job roles since meeting in a bunker during the Second Gulf War. They think more school staff should follow suit …

“There’s nobody more interested in you talking about your work than your job-share partner,” says Heather McNaughton.

She has spent most of the last two decades sharing her job with Caroline Pusey, including in military bunkers for the Ministry of Defence and during strike negotiations as directors at the Department for Education.

The pair earlier this year took up the position of joint chief operating officers at the River Learning Trust, which has 29 schools across Oxfordshire and Swindon.

With teacher wellbeing at its lowest level for five years, and stress, insomnia and burnout all continuing to rise – it’s not the easiest time to work in schools.

But McNaughton says sharing the burden means there is an “inbuilt support and therapy”.

So close is their connection, in fact, that McNaughton’s husband refers to Pusey as her “other husband”.

Going underground

Their first job share (of sorts) was a far cry from the cosy school office they now inhabit.

It involved the pair taking over from each other after gruelling 12-hour shifts in a “little shoe box” bunker three floors underground at the Armed Forces’ Northwood military base in northwest London.

It was the start of the Second Gulf War, and both were on the Civil Service Fast Stream graduate programme. They were tasked with communicating details of operations back to civil servants and ministers in London, to prepare them for media briefings.

Next door was the operations room, where a big screen plotted military movements.

Although it was “immensely challenging”, McNaughton says it taught them “how to job share, because if you can do it in that situation, almost anything else is easier”.

Pusey credits her mum, a Citizens Advice bureau manager, for instilling in her a “commitment to public service”. She spent her childhood in Malvern, Worcs, and later studied International Relations at Birmingham University.

Meanwhile, McNaughton, whose parents were vets, grew up in Birmingham before doing a chemistry doctorate at Oxford.

‘Walking the walk’

After their military bunker spell the pair returned to London – spending the next few years in similar roles looking at how well prepared the Ministry of Defence had been going into war.

Pusey then spent five months in Afghanistan and six months in Iraq, where she led a team of 25 civil servants confined to base in Basra.

Some were in “very emotive” roles processing claims from Iraqi civilians whose families had been injured or killed by British military action.

It was a “formative time” in Pusey’s leadership, when she learned “the importance of walking the walk with my team”.

Meanwhile, McNaughton’s life took a very different turn when she lost her sight for six weeks and was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

She had to learn to become a different type of leader, to “guide and shape”, but “ultimately deliver things through others”.

She believes that her illness “accelerated” her leadership journey, whereas most leaders realise the importance of delegating at a “later stage”.

While on maternity leave to have twins, Pusey took over her MOD role.

Pusey later ended up becoming private secretary to Armed Forces ministers during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, including when the ministry was criticised for sacrificing safety to cut costs after 14 crew were killed in an RAF Nimrod air crash in 2006.

When Pusey returned from her own maternity leave, the pair entered their first job share – as senior civil servants.

They worked mostly on workforce issues – but their proudest achievement was leading on legislative changes allowing part-time working in the armed forces.

Part-time champions

The pair were then promoted to become the MOD’s first ever director-level job share, before moving to the DfE in 2018.

As directors of teaching workforce, they led on work around wellbeing and teacher workload, including creating packages of support and toolkits around making job shares work.

They also oversaw the recruitment and retention strategy in 2019.

Pusey says it had a “real impact” – pointing to the early career framework and new national professional qualifications (and despite the “substantial headwinds” thwarting wider progress).

One of those was Covid.

McNaughton believes there was “very little choice” but for schools to close in the first lockdown because so many school staff were isolating, they “couldn’t operate, even with central guidance”.

Pusey adds it was “hard to separate decisions made around schools from the wider decisions around society as a whole”.

The pair also led on the national tutoring Programme when it was at its “lowest ebb” and got more funding into it. But it fizzled out last year with millions of catch-up cash going unspent by schools that couldn’t afford to chuck in their own funds to access the subsidy.

McNaughton says she now understands better how “leaders have so much on their plate, whatever brilliant initiative DfE comes up with, you’ve just got lots of other things getting in the way”.

Last year the pair launched ‘ambassador’ multi-academy trusts and schools to champion flexible working, and designed toolkits advising school leaders.

But Pusey found getting the resources “into the psyche of those heads-down delivering” was “the hardest thing”, as they’re “so busy dealing with the day to day”.

Striking a balance

The pair were also guilty of overwork themselves, particularly after becoming director general of schools – putting them “front and centre” in strike negotiations.

“We expanded our role too far,” admits Pusey.

Many an education leader would love to have been a fly on the wall, and McNaughton says she could write a book about all they learned at those discussions.

While their role was to “support government”, the six years spent trying to boost recruitment and retention meant they had huge empathy for the unions’ cause.

Did the politicians have that empathy for teachers, too?

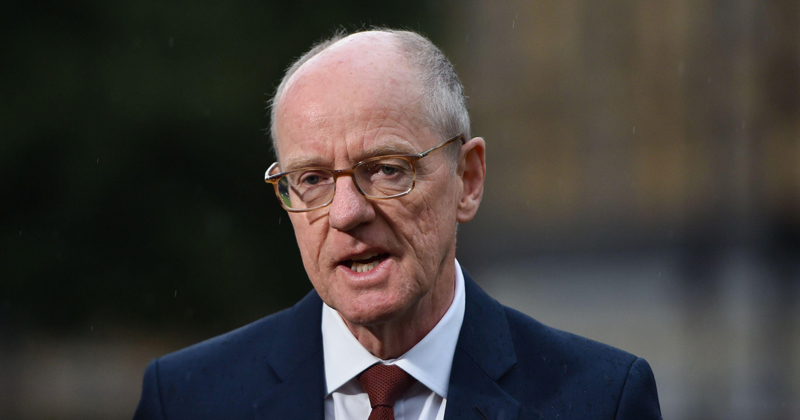

McNaughton says they “had views based on their own upbringing and backgrounds”. But she felt then-schools minister Nick Gibb, “for all that may be said against him, was a man with more empathy than the sector would give him credit for”.

“He was very keen and seeking all avenues to get a resolution,” she adds.

The first six months of last year were a “long, intense” time which left them “pretty tired”.

Afterwards, they took a four-month career break to find a role “closer to frontline delivery”. And in April, they joined the “hugely values driven” River Learning Trust.

Trust life

Their DfE experience gives them a “good contact list” when problems arise, and they “instinctively know” what the department is looking for on issues.

“We can translate guarded messaging,” says McNaughton, and “envisage what’s happening behind the scenes,” adds Pusey.

Pusey commutes from London and McNaughton from Maidenhead, Berks, to their office in Kidlington, Oxon, three days a week, including Wednesdays when they’re both present.

As chief operating officers they’re responsible for all the trust’s back-office functions except finance.

IT and management information changes have kept them busy lately, as well as strategic work managing the process of taking on new schools. They are currently engaging with three schools about joining the trust.

With Pusey and McNaughton paid 0:6 of a full timer, there’s a financial hit to employers allowing job shares which might be putting some off.

A DfE survey last year found that in primaries, only 7 per cent of leaders and 12 per cent of teachers had a job-share in place.

But in secondaries, there were no leaders sharing roles, and only 1 per cent of teachers.

McNaughton points out their trust gets “two brains thinking all week” and “extra energy”.

Pusey also believes the model gives them a “balance” that she doesn’t see in other part-time roles.

While “lots of people are checking their emails while they’re dropping off kids”, she could “dump the work” on her days off from DfE and be “fully with” her kids. “It feels like two personalities, but I love it”.

Pusey believes there’s “absolutely no reason” why job shares can’t work at school leadership level, particularly in primaries, given how the demands of headship are increasing. She vehemently disagrees with the notion she “often” hears that “you can’t have more than one school leader”, because only one can “embody the leadership”.

Where job sharers have different expertise they can “cover more bases”.

But McNaughton has come across less successful job shares in schools which haven’t been invested in properly, with no delegated handover time, for example.

She says you need to be prepared to “surrender” your ego to the partnership; there are times in their current role when one gets praised for work the other has spearheaded, or one has to fix what the other has “screwed up”.

“We stand and fall on each other’s actions.”

Another key lesson they’ve learnt is that, as with parenthood, “you don’t argue in front of the children,” says McNaughton. That means they “present a united front and would never undermine each other” in front of their team.

In the same way that their legacy at the MoD was introducing part-time working within the armed forces, they both hope to have enabled and inspired more school staff to work flexibly.

“The cultural journey the education sector is on is longer term, but critical,” adds McNaughton. “We’re absolutely committed to it.”